An award-winning journalist, Katie has written for Chicago Health since 2016 and currently serves as Editor-in-Chief.

Street medicine is changing the way medical providers deliver care — meeting unhoused older adults where they are.

This is part 3 in a 4-part series on older adults and homelessness. Read part 2 here about women and homelessness and part 1 here.

On any given night, the small team at The Night Ministry packs their gear — food, water, wound care supplies, and more — into a customized van. Over the next five hours, they’ll visit tent encampments and bus and train stations, offering basic supplies and medical support to Chicago’s unhoused people.

“The Night Ministry!” The team calls out at each stop. “Food, healthcare, anything else you need?”

Through this street medicine (or backpack medicine) approach, the team will treat about 50 people in a shift, with 18% of the patients over age 60. More coordinated medical efforts than ever are treating people outside of traditional healthcare settings — California alone has at least 25 street medicine teams — and they’re reaching a growing population of people who often mistrust traditional healthcare settings, due to discrimination or mistreatment.

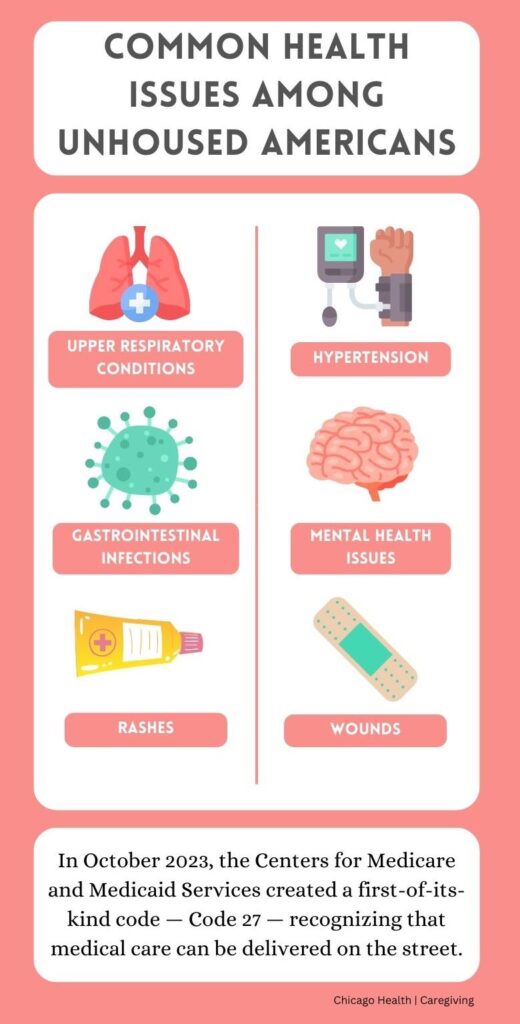

In a typical outing, The Night Ministry team sees wounds, gastrointestinal issues, rashes, and upper respiratory infections. They also see chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and mental health. Medical staff provide support on site through medications and assessments, but if a person needs further attention, the team will drive them to a local emergency department.

“We have a nonjudgmental approach because if we shame people, that’s not going to build a bridge or help toward any progress,” says David Wywialowski, outreach and health ministry director at the nonprofit.

In the unhoused population, diabetes, heart disease, and HIV/AIDS are three to six times higher than among the general population, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness. Many people living outdoors also experience what researchers call accelerated aging. This happens when a person’s physical age surpasses their chronological age due to constant exposure to the elements, lack of healthcare, inadequate nutrition and hydration, stress, poverty, discrimination, and more.

“These could be individuals who were strong, contributing members of society at one point, and because of what’s happened to them, they can’t get back to that place of stability,” says geriatrician Jay Bhatt, DO.

Bhatt worked on this issue as managing deputy commissioner with the Chicago Department of Public Health from 2013 to 2015. Now managing director of the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions and the Deloitte Health Equity Institute, he looks at the homelessness crisis not only as a physician but also from a healthy equity and economic perspective.

Black and Latino populations are disproportionately impacted. “The wealth gap leads to a health gap,” Bhatt says. “Not having economic opportunities leads to unstable housing and poorer health.”

He sees efforts such as street medicine and other investments in preventative medicine as part of the solution. “Proactively investing in health instead of waiting for patients to become sick can really be a game changer,” Bhatt adds. “You just have to have both the leadership will and the execution to make it happen.”

The Night Ministry street medicine team, started in 2015, consists of about five people: a physician volunteer or full-time nurse practitioner, case manager, substance use specialist, psychiatrist nurse practitioner, and an outreach worker who has experienced being unhoused. The outreach worker can say, “Listen — I have been where you’re at. You can trust these people.”

Often, people on the street have already heard about The Night Ministry from others or from the organization’s history stretching back to the 1970s. In 1976, 18 congregations in Chicago joined together and hired a minister to do homeless outreach in the Lakeview area. For the next decade, the minister reported back about the needs he saw, and the congregations tried to meet those needs.

The Night Ministry grew — purchasing an outreach bus and hiring a team of employees. When the organization started its street medicine program, Wywialowski connected with Pittsburgh’s Street Medicine Institute for training.

“We’re not alone in doing this, and we don’t have to reinvent the wheel,” Wywialowski says.

Birth of street medicine

Pittsburgh’s internationally recognized program began in 1992 with one concerned physician and a formerly unhoused person who acted as his liaison as he made medical visits to people living on the streets. Jim Withers, MD, saw unhoused people as excluded from mainstream healthcare systems despite higher rates of illness and premature death, according to the Street Medicine Institute’s website.

Through his visits, Withers realized that the traditional health system wasn’t adapting to unhoused people’s needs or circumstances. Withers referred to his approach as “reality-based medicine.”

He traveled throughout the U.S. and abroad to observe how other physicians approached medical care for the unhoused. He discovered that the physicians tended to work in isolation. Neither the physicians’ peers nor their medical institutions recognized the work.

Withers, however, did. He linked together the practitioners working in isolation and in 2005 founded the International Street Medicine Symposium. It has met annually since to share ideas and validate work. And the Street Medicine Institute gained nonprofit status in 2009, expanding into an international network in more than 85 cities and 15 countries on five continents.

“It’s a global movement. People around the world want to help people who are unhoused,” Wywialowski says.

A blossoming movement

In 2016, medical students at the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) started their own street medicine organization — Chicago Street Medicine — to respond to the need they saw throughout the city.

“Medical students have the time and energy to plan and establish the infrastructure. When we approach attending [physicians], they immediately understand the need and are willing to offer support,” says Reba Abraham, PhD, a medical student at the University of Chicago and vice president of operations for Chicago Street Medicine.

The group now has four chapters at medical schools throughout the city: UIC, University of Chicago, Loyola Medicine, and Northwestern Medicine. Each chapter goes out once or twice a week.

Student-led street medicine efforts aren’t unique to Chicago. At a meeting of the American Medical Association (AMA) this past fall in Maryland, medical students from Texas and New Jersey led a panel about street medicine. Then, with a grant from the AMA Foundation, attendees assembled 100 care kits for the organization Street Health DC. They filled the kits with over-the-counter medications, hand warmers, hygiene products, and more.

Third-year medical student Anand Singh, at Texas Christian University, was a lead author on an AMA policy advocating for Medicare and Medicaid to recognize that medical care can be delivered on the street.

In October 2023, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services took up that policy, creating a first-of-its-kind code — Code 27 — that describes “a non-permanent location on the street or found environment, not described by any other [place-of-service] code, where health professionals provide preventive, screening, diagnostic, and/or treatment services to unsheltered homeless individuals.”

In a letter to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in appreciation of the new code, James Madara, MD, CEO of the AMA, asked that the department go a step further. “We encourage you and your colleagues to provide physician education about this new [place-of-service] code to ensure it is widely used,” Madara wrote.

Chicago Street Medicine’s work centers on breaking down the barriers to care that drove Withers’ early work. “A lot of what we do is trying to give them a bridge to access traditional healthcare,” Abraham says. Bus passes and paperwork help build that bridge.

“Navigating healthcare is really daunting even when you have stable housing and reliable income,” Abraham says, adding, “We don’t manage people’s chronic conditions on the street, but we want to make those admin barriers a little less so they can access healthcare.”

In 2022, Chicago Street Medicine made 951 clinical visits. Similar to The Night Ministry, Abraham says that their underlying theme is to go where the people are.

The group typically includes medical students, residents, an attending physician, and occasionally a specialist, such as a podiatrist, occupational therapist, or social worker. Regardless of who goes on a given run, Abraham says they treat all people they encounter with respect.“We treat every tent, every bed setup, as if it’s someone’s home.”

This makes a difference because many of the unhoused individuals say that the traditional healthcare system has shamed or mistreated them. “Many have had negative interactions within the healthcare system, so when we’re coming to them and establishing that rapport, it’s a more positive interaction,” Abraham says. “When we show up week after week, people start to trust.”

Older — and sicker

That trust is necessary now more than ever. With more people — and more older adults — unhoused, the increase in extreme weather events such as heat waves and flooding put more people at risk for health crises.

That trust is necessary now more than ever. With more people — and more older adults — unhoused, the increase in extreme weather events such as heat waves and flooding put more people at risk for health crises.

“Environmental conditions are getting harsher, and it’s harder to be in environments that weren’t as harsh before,” Bhatt says. “This is such an important issue, and what gets lost is how much it impacts older adults, who are spending their later years, maybe even their last years of life, outdoors or in shelters.”

Extreme heat, for example, leads to a 17% increase in emergency department visits. Poor air quality days often see a similar increase. “Some of the extreme weather conditions will hit [the unsheltered] population in an accelerated fashion and particularly if they have other conditions — even worse,” Bhatt says.

Without the stability of a home, those conditions have a greater impact. Nearly 30% of people over age 65 have diabetes, according to the American Diabetes Association. If they’re unhoused, Bhatt asks, “Where do they store the insulin if they need insulin?”

Living outdoors is a life of scarcity and competing priorities. As people juggle the need for safety and basic resources such as food, water, and shelter, easily preventable or treatable health issues land them in the hospital.

“If you don’t know where you’re sleeping at night, it’s impossible to meet any other need. How can you think about anything else?” asks Beth Horwitz, vice president of strategy and innovation for the nonprofit All Chicago Making Homelessness History.

Another challenge among the unhoused population is unaddressed mental health issues.

An estimated 30% of people experiencing homelessness have a mental health condition. And the country is experiencing a severe shortage of mental health professionals. Illinois, for example, has only about 14 behavioral health specialists — such as counselors, therapists, psychiatrists — for every 10,000 residents. This means that 4.8 million Illinois residents live in a mental health professional shortage area. The shortage leaves people without access to care, increases hospital stays, and stresses systems.

“People don’t have the right support they need to work through the challenges we have in life. I think we can and should do better,” Bhatt says.

Substance use, a mental health disorder, tends to be more prevalent among the unhoused than the general population, according to the National Coalition for the Homeless.

“People think: You use substances and are therefore on the street, not that you’re on the street and therefore using substances,” Horwitz says. “Being on the street is potentially one of the hardest things you could go through, so using substances is a coping mechanism.”

Wywialowski adds that The Night Ministry supports people where they are. “If people are ready for detox and rehab, we can connect them. If they’re not ready, then we are with them during this journey they are on.”

The Night Ministry tries to be there for their workers, too. “We do a lot to support our team because they are seeing trauma each day that they go out,” Wywialowski says. At monthly employee events, “We just try to have some fun together so we can continue to do the work we do.”

Housing as healthcare

Wywialowski has been at this work for 25 years. He started with The Night Ministry as an outreach worker in Lakeview. On Tuesday and Thursday nights, from 8 p.m. to 2 a.m., he would walk with a backpack on, carrying trail mix, water, and hygiene supplies. “I would just talk to people panhandling about what’s going on in their life,” he says.

Now, he says, “We’re doing more outreach and touching more lives than ever before.”

Many see housing as the answer, including Bhatt and Abraham. In fact, on average, people with stable housing live 27 years longer than people without housing.

“It’s tough when you have this community of patients going in and out of services. When you get them housed, that’s when you make some progress. They can get counseling, get enrolled in programs if there’s a consistent relationship,” Bhatt says. “Housing is health.”

It’s also the no. 1 concern Abraham hears from the people she meets on the street. “We ask if there are things we could’ve brought that we didn’t or services they’d like to see. And its always, ‘I just need housing,’” Abraham says. “I’d love to see a smoother path to get people into housing — making the process more accessible and shorter.”

Bhatt sees the current state of unhoused Americans as a form of moral failure. “We’ve had a history of economic, educational, and housing policies that put people at risk of being disproportionately impacted,” he says. “Better health for everyone is not only a moral imperative but an economic imperative.”

Angel, who stays in a bright orange tent in Humboldt Park, sees it as life. “There’s a lot of people out here who are hurting. Some of them are strung out on drugs or alcoholic, but they need help because without help, all they’re gonna do is keep sinking deeper and die.”

He says he’s seen a few people die already. “They needed help — physical, mental, all that.”

And Angel tries to help, he adds, shaking his head. “But I’m hurting, too.”

—

This series is published as a partnership between Caregiving Magazine and Chicago Health Magazine. It was written with the support of a journalism fellowship from The Gerontological Society of America, The Journalists Network on Generations, and The John A. Hartford Foundation.

Series illustration by Dan Leu. Main photo by Jim Vondruska.