An award-winning journalist, Katie has written for Chicago Health since 2016 and currently serves as Editor-in-Chief.

Older adults face an increased risk for homelessness across the U.S. As many people search for solutions, they’re also asking themselves what it means as a society when we can’t care for our most vulnerable.

This is part 1 in a 4-part series on older adults and homelessness. Read part 2 here about women and homelessness. Part 3 explores how street medicine meets older adults where they are.

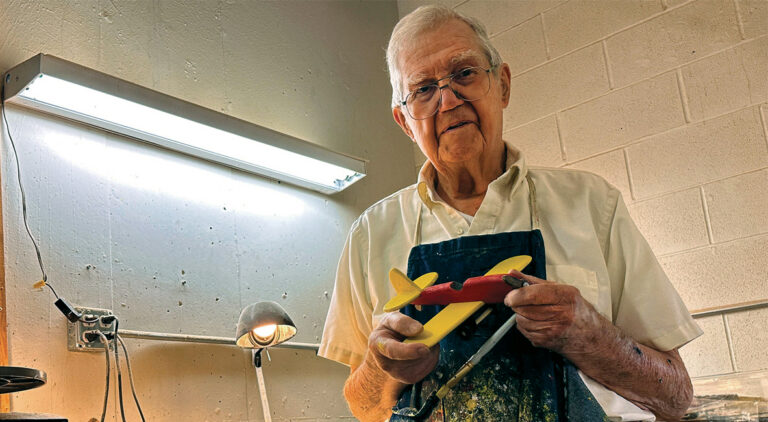

Angel doesn’t need the scars to remind him. He remembers the day it happened, how the man pulled up along Humboldt Park one morning seven years ago, asking if anyone wanted to make a few bucks by helping him move. Angel was in his early 50s at the time, living on and off in the park. He readily agreed to help and hoped to earn enough to get something to eat that day.

At the residence near Augusta Boulevard and Ridgeway Avenue, the man asked Angel to dispose of a box of unwanted items in the alley garbage bins. The box wasn’t too heavy, but in the alley, when Angel stepped on the edge of a pothole instead of on flat ground, he pitched forward. His knee snapped.

“When it snapped, I freaked out and let go of whatever I had. I put all my weight to the other leg, and it snapped going the other way,” he says. In shock, Angel collapsed.

Angel tried to get up but couldn’t move his legs. He screamed for help. A bystander took him to the hospital, where Angel remembers the doctor’s astonishment. “Wow, you have some crummy luck,” the emergency physician told him.

Meanwhile, the man who’d asked for moving help disappeared. “I don’t know who they were, the name, nothing,” Angel says. “He just came to the park asking if people wanted to make a few dollars. Who would think you’re going to break both of your legs? That’s been my s*** life so far.”

Angel’s brother and sister-in-law took him in while he recovered, but as happens with many people who live on the streets, follow-up care falls by the wayside against competing demands for basic needs like food, shelter, and water. Angel never underwent physical therapy to rebuild his leg strength, and he still struggles with intense pain nearly a decade later.

“My nerves — they kill me. Sometimes I don’t feel this side of my leg. Sometimes I get a shock so bad it goes to my back. It’s kind of hard to get around,” he says.

More than a place to live

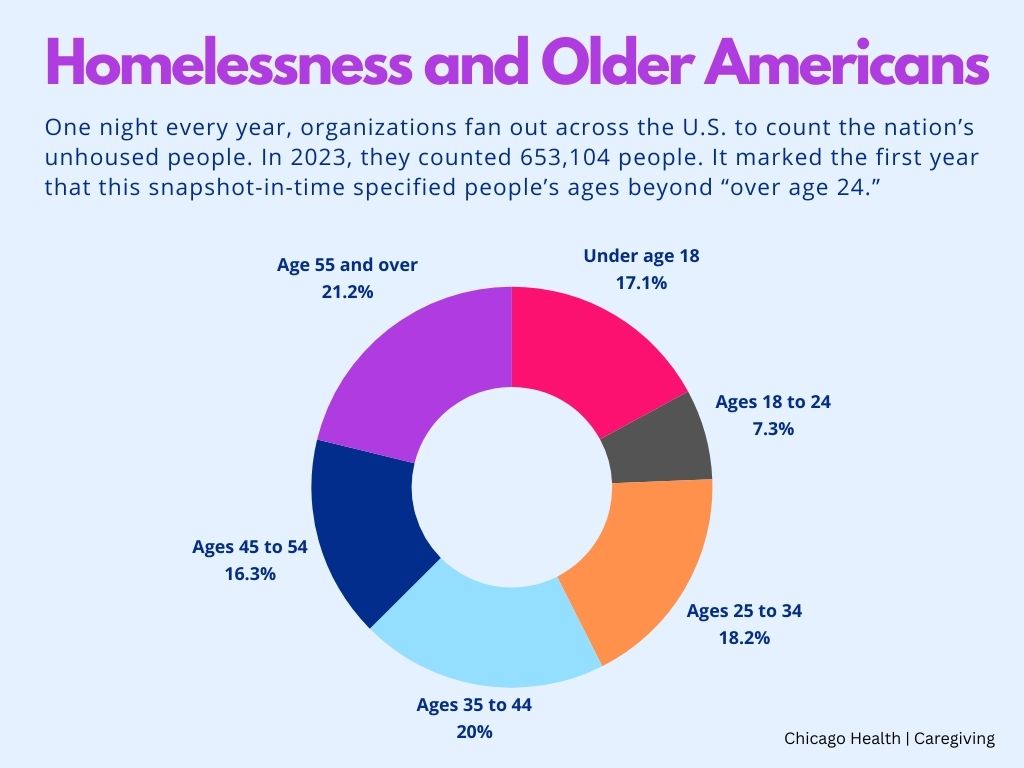

Angel is one of 653,104 people experiencing homelessness in the U.S., according to the 2023 Homeless Assessment Report. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) released the report in December. And that very specific number comes from the annual point-in-time count, when organizations in cities across the U.S. fan out over a single night in January, tallying the people living in shelters and on the streets.

Their findings show that from 2022 to 2023, homelessness increased by 12% in the U.S. That increase bucks trends from the decade prior, when from 2010 to 2016 the nation saw a decrease in homelessness. In a February webinar discussing the report, Jeff Olivet, executive director of the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, attributed the previous drop to federal investments in housing, focusing on veterans and youth especially.

And for Olivet, housing is a clear solution, especially for people in situations like Angel’s, who need follow-up healthcare.

“Housing is healthcare. It’s the prescription that can solve basic homelessness for people,” Olivet said in the webinar.

He added that he believes down to his core that homelessness is solvable. “I believe that because it hasn’t always been this way. We’re in a crisis right now — let’s make no mistake about that. Homelessness is the failure of systems, not individuals. There’s not one county in this country where people can afford a 2-bedroom apartment on minimum wage.”

Beth Horwitz is vice president of strategy and innovation at nonprofit All Chicago Making Homelessness History — the central coordinating body around homelessness in Chicago. She sees access to affordable housing as a key challenge.

“If you think about what market economics would say to us, there’s not enough housing at the right price. We either need to figure out how to raise wages so when you’re working a minimum-wage job, you can afford housing in the local market. Or we need to figure out how to make housing more affordable,” Horwitz says.

Older adults face another housing challenge, though, because they tend to be on fixed incomes. “So as their housing costs change, they’re at risk of not having enough income to change their costs,” Horwitz says. “You can imagine that if you get an unexpected bill or raised rent, that is imperiling to seniors.”

Fixed income adds to the risk

Of all people experiencing homelessness in the 2023 count, 138,089 were over age 55. The 2023 report showed overall that older Americans were, in many places, becoming the fastest growing segment of the homeless population.

In Chicago, however, their numbers remain steady at about 5% — or 800 people.

“We know that for so many, homelessness happens because of an unexpected payment issue: The car needs repairs, or there’s a medical bill. An expense comes along, and you’re not prepared to weather the storm,” Horwitz says.

The expense doesn’t need to be large, either. “A really bad recipe for disaster is when you’re on a fixed income, and rent goes up by $200,” Olivet said. When people are already facing difficult financial decisions around food and medications (older adults also tend to have more complex medical issues), “It doesn’t take much for people to slip over the edge.”

A triggering event can leave older adults vulnerable to homelessness, too. Maybe a spouse passes away unexpectedly or a couple goes through a divorce. The person loses emotional support, a second income, and a sense of security.

Scenarios like this are in part why Horwitz sees homelessness as the result of inadequate community and systemic supports. “Homelessness is the result of lack of social safety net and not living in community,” she says.

The tent encampments lining expressway underpasses and public parks reflect America’s values. “We seem to collectively be okay with it that not everyone gets to be housed,” Horwitz says. She, however, is not. “That’s not [a society] where I want to live, which is why I work on this issue. It’s about how we pay people, and how we figure out what it costs to be housed.”

As bikers cruised through Humboldt Park on a sunny weekday morning and nannies pushed strollers along the path, Angel gathered with a group of friends in his tent area — all men, joking and laughing, thankful for a warm February. To the east: the streets where Angel had grown up: Rockwell and Le Moyne Streets. “So I know the area very well,” he says with a laugh.

Just beyond Angel’s group, an older woman with dark hair silently swept the area outside her tent, tears streaming down her face. She had just moved in but never expected to be there, she said, and she wasn’t ready to talk about it.

—

This series is published as a partnership between Caregiving Magazine and Chicago Health Magazine. It was written with the support of a journalism fellowship from The Gerontological Society of America, The Journalists Network on Generations, and The John A. Hartford Foundation.

Series illustration by Dan Leu.