Katie Colt is a writer living in the Chicago area. Her work can be found at The Huffington Post, The Washington Post, and more.

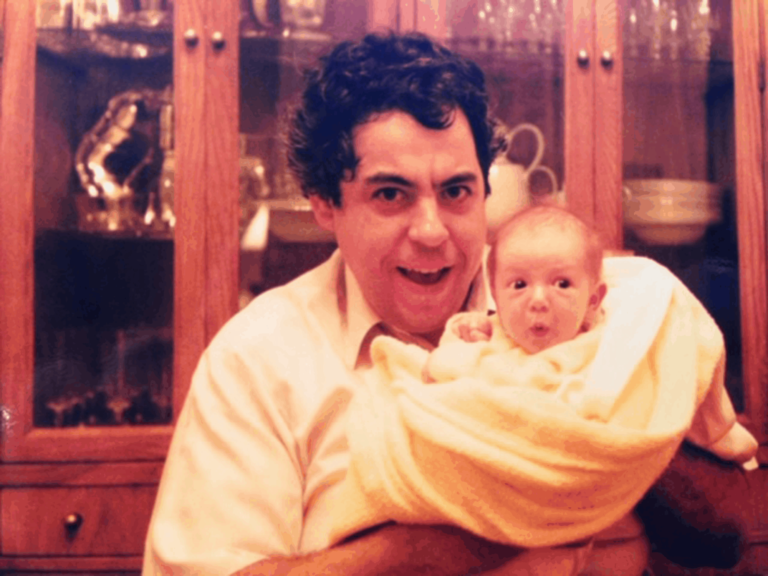

Above photo: Writer Katie Colt, as a baby with her father Norman Sack. Photo courtesy of Katie Colt

My mother recently received a call from my father’s memory care facility in northern Cook County, letting her know that he had tested positive for COVID-19 — the facility’s first known positive case. I don’t know with certainty what the next several days or weeks will look like for my dad, but given the trajectory of the virus for people in his situation, I have a realistic picture: It will be agonizing.

We are full of anxiety and anguish, as so much of his condition changes from day to day, sometimes predictably and sometimes not. And yet, I hope and wait and watch against the possibility of his death. His dementia diagnosis has meant that I’ve been saying goodbye to him — and to who he’s been — for several years now, but none of that has prepared me for the possibility that the next phone call may bring the news that I’ll never see him again.

The staff is vigilantly watching too. Since announcing its lockdown on March 13, his memory care community has been fastidious about monitoring residents’ vitals, checking incoming staff members for symptoms daily and sanitizing surfaces almost hourly. They had been monitoring my dad, suspecting he had a urinary tract infection or kidney infection, because he had a low fever, complained of some back pain and was a bit more uncooperative than usual. And then he tested positive for COVID-19.

Now, with a confirmed resident infection, they are isolating my dad and preparing to isolate other residents who become symptomatic. This is especially heartbreaking for him, given that his regular daily interactions with other community members and staff members encourage his mental engagement.

With current COVID-19 precautions, his interaction is limited to seeing a few staff members every few hours. With his dementia, he may not recognize them, covered up in masks, gowns and other personal protective equipment.

I’ve talked to my dad twice on the phone since he was moved to the facility’s makeshift isolation wing. He needs assistance to operate a cell phone, as he’s forgotten how to use one. He has heard of the coronavirus, but it is not clear whether he really understands that he has it.

When we spoke, he was his typical upbeat self — an inherent personality trait I’m grateful is still intact — but he was more confused than usual, slurring words and trailing off mid-thought. I’m worried that the virus has caused additional irreparable damage to his cognition.

Amid this increased confusion, another unfortunate side effect of the virus has been that he’s forgotten how to walk. It’s unclear whether this is directly related to his dementia, COVID-19 or isolation, but he has been bedridden, which places him at increased risk of complications. Currently, hospice nursing has been called in to help handle his newly immobilized state.

It’s another daunting transition that has been thrust upon us, having spent the past six months getting used to his new home and our new family situation. My dad had suffered from dementia with increasing severity for nearly a decade. In October, my mom made the heart-wrenching decision to move my dad, her partner of more than 40 years, into a memory care facility.

Up until COVID-19 struck, my mother made it her mission to visit him every day, joining him for meals and activities and bringing his clothes home to launder herself. I visited my dad, taking him for drives and quick trips to the beach, listening to the radio together and reminiscing about pieces of his past I hoped he might remember.

And then, just as we had begun adjusting to the situation, COVID-19 struck our society, especially affecting older adults with chronic health conditions who were like sitting ducks in nursing homes and senior care facilities. Then we got the call. The news of my father’s positive test was not a shock to me — it felt inevitable, like a confirming stamp of doom.

The facility’s staff has been incredibly responsive to our concerns and requests for updates. My mom speaks with his nurses daily and checks in with other caregiving staff as questions arise. I talked to the director, who has spent hours on the phone with concerned families and has dutifully handled the panic and fear from staff.

In the face of the unfolding pandemic, 70% of the staff is still working, taking proper precautions and caring for residents. The remaining 30% have stopped coming to work. I understand that people have to protect themselves, and the cost of leaving their job behind is not as great as losing their lives. But when they leave the job, the patients are left behind, too.

So all I can do now — quarantined at home myself, unable to share a laugh and sing a song with my father, prohibited from being by his side at his most vulnerable time — is to love him from afar and to encourage others to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Assume you already have COVID-19. Assume that, despite your good health and lack of symptoms, you have the ability to pass it on to anyone you share the same air with, 6 feet away or not. If you are able to quarantine at home, stay home.

This assumption will save lives. It will halt transmission to the first responders and healthcare professionals whom our society depends on most, among them the kind, dedicated and talented individuals who take care of my dad and others with dementia and advanced disease.

Follow the guidelines outlined by public health officials. Act in preparation for the worst.

And, like me, hope for the best.