Karen Purze is an author based in Chicago, IL. She writes about end-of-life planning and family caregiving at lifeinmotionguide.com.

What happens to your online accounts, photos, and files after you die?

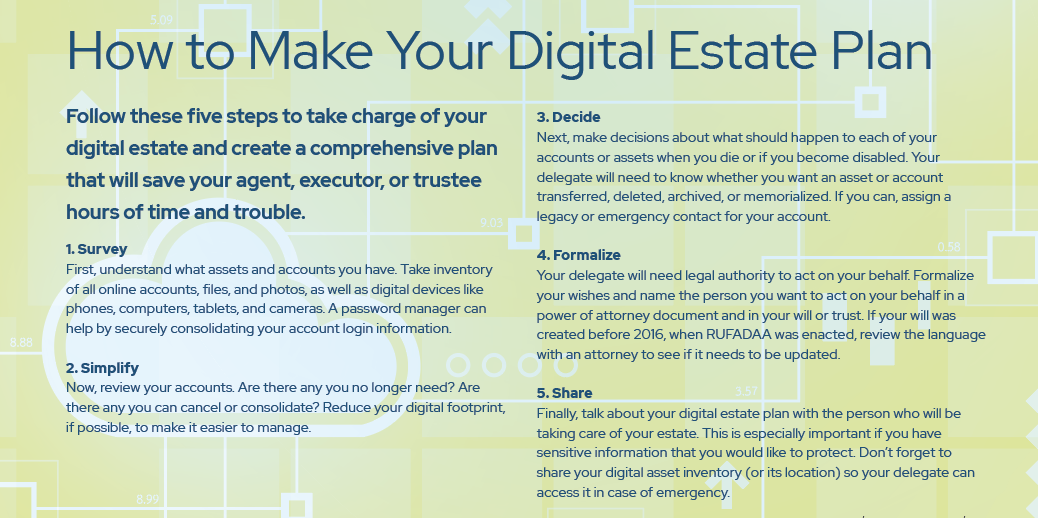

Imagine if, at the time of your death, someone had to secure every digital asset that you owned or controlled. How easy — or hard — would that be? Most of us have digital assets and subscriptions. In fact, according to a Harris Poll study conducted in partnership with Google, the average American has 27 online accounts that require passwords.

Digital estate planning enables you to protect your social media accounts, digital currencies, photos, files, and other properties stored digitally. Some attorneys suggest real assets that can be accessed digitally (like money in a bank account) also be included in the scope of digital estate planning.

“Access to digital asset information needs to be a part of every estate-planning conversation,” says Fredrick Weber, an estate attorney and senior wealth adviser for the national estate settlement services practice at Northern Trust.

“People should create and maintain a detailed list of all of their asset and liability information, update the list regularly, and store it in a secure place where it can be accessed post-death by their executor or someone they trust,” he says.

That access and information are increasingly important, says Linda Strohschein, attorney and owner at Strohschein Law Group, a Chicago-based law firm focused on estate and long-term care planning.

“Twenty years ago, when someone died, I’d say go change the lock [on the house], collect the bills, and find bank statements and paperwork in the house. We don’t have that anymore. We don’t have [only] the physical file cabinet anymore, and that makes it harder to find everything,” she says.

Granting access

Illinois, like most states, has enacted the Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act (RUFADAA), which provides a statutory framework for executors to obtain access to asset information stored on certain digital platforms (in a Gmail account, for example) following a death.

There is a caveat, though. Your executor can only be granted access if your will specifically authorizes your executor to access your digital asset information after your death.

Ensure your delegate has legal authority to act on your behalf by including language in your power of attorney and in your will or trust documents, Strohschein says. She also recommends taking an additional step: “The most important thing is to give access to your primary email and to your phone.” With those accounts, your delegate can re-create access to other accounts after your death by resetting passwords, she says.

Giving guidance

Once you’ve ensured someone you trust will have legal access to your accounts, it’s important to make sure they know what you want to happen with the assets, such as whether an asset or account should be transferred, deleted, archived, or memorialized.

Kerry Peck, managing partner at Peck Ritchey, LLC, a Chicago-based law firm that concentrates on trust and estate litigation, warns, “There’s a learning curve with all this.” Each account is governed by different terms and conditions, he says, so you’ll want to review each account’s user agreement before you decide how you want to handle it.

Getting it done

If the thought of getting your digital accounts organized and documented is overwhelming, you’re not alone. Kristyn Ivey, a Chicago-based professional organizer, says her clients focus far more on physical organizing than digital.

“I think that’s because digital clutter can feel limitless or intangible,” she says. “It’s easy to get overwhelmed, and it’s easy to move it down the priority list because it’s abstract.” She recommends first starting with the easier tasks, or quick wins, rather than procrastinating further.

Naperville native Mike Donnary started organizing his accounts with a digital inventory list from his estate attorney. He and his wife each spent about an hour documenting their most important accounts. They also used the Mint app to capture smaller accounts, such as PayPal, as well as other assets, such as cars and motorcycles, so everything was in one place.

“Once we shared this information and approach with our daughters, who are 22 and 19, they seem to be heading into adulthood with a much better understanding of finances than we had,” Donnary says.

While it may seem tedious, gathering this information is critically important. If not documented, Weber explains, “The cost of identifying and locating assets post-death could increase significantly, particularly if the executor has to hire professionals to gain access to a locked computer or help track down missing assets.”

Just as importantly, he says, “If assets get missed or are not found during the post-death administration process, they cannot be distributed to the intended beneficiaries.”