While there are more than 100 types of arthritis, osteoarthritis is by far the most common.

Osteoarthritis is the form of joint disease that’s often called “wear-and-tear” or “age-related,” although it’s more complicated than that. While it tends to affect older adults, it is not a matter of “wearing out” your joints the way tires on your car wear out over time. Your genes, your weight, and other factors contribute to the development of osteoarthritis. Since genes don’t change quickly across populations, the rise in prevalence of osteoarthritis in recent generations suggests an environmental factor, such as activity, diet or weight.

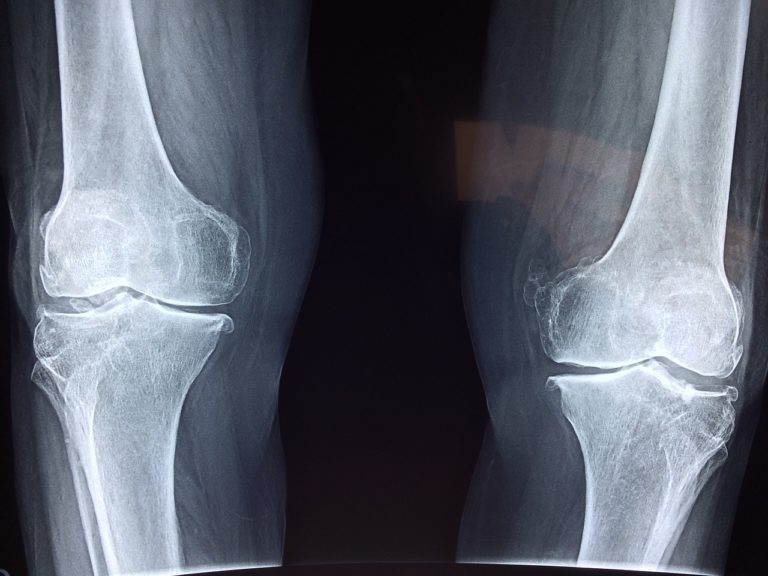

Knee osteoarthritis will affect at least half of people in their lifetime, and is the main reason more than 700,000 people need knee replacements each year in the U.S.

The obesity-arthritis connection

To explain the rise in the prevalence of osteoarthritis in recent decades, most experts proposed that it was due to people living longer and the “epidemic of obesity,” since excess weight is a known risk factor for osteoarthritis. Studies have shown not only that the risk of joint disease rises with weight, but also that even modest weight loss can lessen joint symptoms and in some cases allow a person to avoid surgery.

But a remarkable study suggests there is more to the story.

Challenging a common assumption

Researchers publishing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences examined skeletons from people who had died and donated their bodies to research. Information regarding presence of knee osteoarthritis, age at death, body mass index (BMI), cause of death, and other data were compared for more than 1,500 people who died between 1905 and 1940 (the “early industrial group”) and more than 800 people who died between 1976 and 2015 (the “post-industrial group”).

A third group of skeletons obtained from archeological sites were also assessed for osteoarthritis of the knee. They came from prehistoric hunter-gatherers living hundreds to thousands of years ago, and early farmers living between 900 and 300 BP. BMI could not be determined for these individuals, but gender could be determined and age was estimated based on features of their skeletons.

The findings were intriguing:

- The prehistoric skeletons and early 1900s cadavers had similar rates of knee osteoarthritis: 6 percent for the former and 8 percent for the latter.

- With a prevalence of 16 percent, the more recent skeletons had at least double the rate of knee osteoarthritis as those living in centuries past.

- Even after accounting for age, BMI, and other relevant information, those in the post-industrial group had more than twice the rate of knee osteoarthritis as those in the early industrial group.

Limitations of this study include BMI estimates at the time of death that might not reflect body weight during most of the person’s life, a study population (bodies donated for medical research or from archeological digs) that might not be representative of the population at large, and lack of accurate information regarding diet, activity, and other important factors. Even so, the findings shake some long-held assumptions and make the rise in osteoarthritis in recent years more mysterious than before.

So what?

These findings call into question assumptions about the reasons osteoarthritis is becoming more common. And they suggest that slowing or reversing the dramatic increase in obesity in recent years may not have as much of an impact on knee osteoarthritis as we’d thought. Finally, if longevity and excess weight do not account for the rising rates of knee osteoarthritis, what does? The list of possibilities is long, and as suggested by the authors of this study includes:

- Injury

- Wearing high-heeled shoes (yes, there is at least one study suggesting that the altered forces in the knee among those wearing high-heeled shoes might contribute to the development of osteoarthritis)

- Inactivity

- Walking on hard pavement

- Inflammation (worsened by inactivity, modern diets, and obesity)

The bottom line

As is so often the case in medical research, this new study raises more questions than it answers. We’ll need a better understanding of why and how osteoarthritis develops before we can prevent it or improve its treatment. There are already many dedicated researchers exploring these important questions.

(Robert H. Shmerling, M.D., is faculty editor of Harvard Health Publications.)