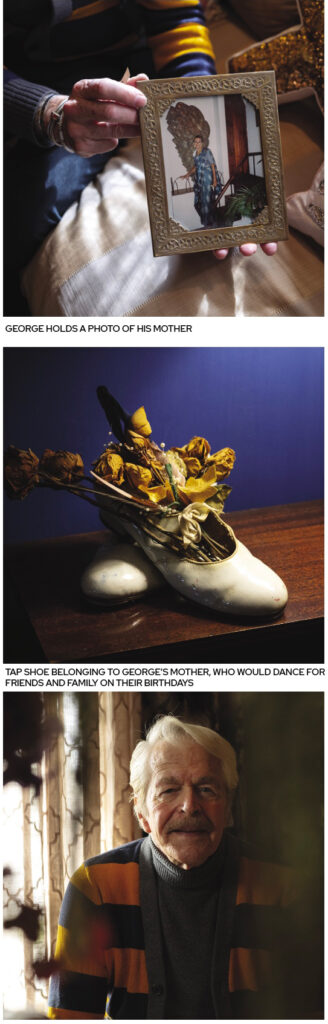

After a long career working overseas, George returned to the U.S. to move in with his mother. She passed away in 2016, two years after being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. George, who is single and an only child, did everything for her: providing personal care, meals, and transportation.

Caring for his mom changed their relationship, with George becoming the parent in a way. However, he adds, “It didn’t affect the quality of the relationship. It was just a redefining of the bond. It was kind of an honor to do it because of what my mother had done for me during her life. I never felt it was an imposition.”

At the same time, George was fully aware of potential caregiver burnout. “I made sure when I needed to, I would have someone come in to take over for me for a short period of time for me to recharge my battery,” he says. A neighbor stayed with his mother sometimes, and an agency also provided respite care a couple of times. When his mother’s condition progressed to the point where she would be safe at home alone in bed, George would make sure to go out briefly each day. “I was aware that for me to be at my best I needed a little free time here and there,” he says.

Now, George also helps anywhere from two to five neighbors, who are friends. For instance, he touches base with a 96-year-old neighbor daily to see if she needs anything from the store or to take her to medical appointments. “It’s all about karma, and somewhere along the line I think maybe I’m gonna be in need of help,” George says.

Now, George also helps anywhere from two to five neighbors, who are friends. For instance, he touches base with a 96-year-old neighbor daily to see if she needs anything from the store or to take her to medical appointments. “It’s all about karma, and somewhere along the line I think maybe I’m gonna be in need of help,” George says.

Utilizing Resources

Shortly after his mother passed away, George remembers feeling depressed and reaching out to the social worker at the senior center. He remembers attending a caregiver support group offered at a local hospital. When that group dissolved, he joined a different support group.

“It’s’ all about karma, and somewhere along the line I think maybe I’m gonna be in need of help.”

Before that group started, he had meetings with the social worker and felt supported because, he says, “she was there for me as long as I needed her.” He describes the social worker, who leads the support group, as someone who “knows the resources, who to contact.” In support group meetings, George asks a lot of the questions and facilitates the meetings’ beginnings.

He says support groups help because everyone is at different stages of their caregiving journey, and can offer insights to guide others. However, he adds, “The primary benefit of a support group is when you hear your story coming out of somebody else’s mouth.”

What Policymakers and Society Need to Know

George feels that support groups like the one he attends need to be better publicized and accessible because, in his experience, many of the people who attended learned about the support group through word-of-mouth. He recently heard about an outreach program that goes to the homes of people who can’t get out — an “amazing resource,” he says, especially because some caregivers need to bring the care recipient with them to support group meetings when they have no one who can take over care. He finds it difficult to share caregiving experiences when a care recipient is also at the meeting.

George says that our society needs to recognize the rolethat caregivers play. Caregiving, he adds, plays an important role in our society and is as inevitable as aging.