Harvard Health Blog

It’s a bit like clockwork: Soon after an important scientific finding about health, a slew of self-help products arrive to support it. Added sugars are unhealthy? Try this diet. A sedentary lifestyle leads to disease? Do this workout. So it’s not surprising that increasing knowledge about DNA markers for longevity called telomeres has spawned yet another round of self-help tools. The latest encourages you to measure the stuff via doctor’s office or a home kit. But should you?

Telomeres and aging

Telomeres are strings of DNA that protect the ends of chromosomes. Telomeres tend to shorten over time as they do their job, so they’re considered biological markers of aging. Unhealthy lifestyle habits — such as smoking, eating junk food, obesity, inactivity and chronic stress — are also associated with shorter telomeres. Shorter telomeres, in turn, are associated with a lower life expectancy and higher rates of developing chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease.

Telomere testing to show biological aging?

According to telomere testing companies, learning your telomere length might provide insight into your “biological” age.

You’ll find the tests in several places. One is the internet. For as little as $100, some companies will sell you a home kit that allows you to send your DNA (in a drop of blood or a cheek swab) to a lab. After a few weeks, the company mails you the test results, which tell you what your telomere length is and how that length compares to your peers.

For more money, you can talk to a company “coach,” who explains the results to you and helps you come up with a plan for healthier living.

Other (more expensive) ways to get the test include:

–going to a walk-in clinic with a doctor who’ll order the test for you and then talk you through the results

–buying and ordering a test from a company that directs you to a lab or a doctor who works in your area

–asking your own physician to order the test for you.

What the tests don’t tell you

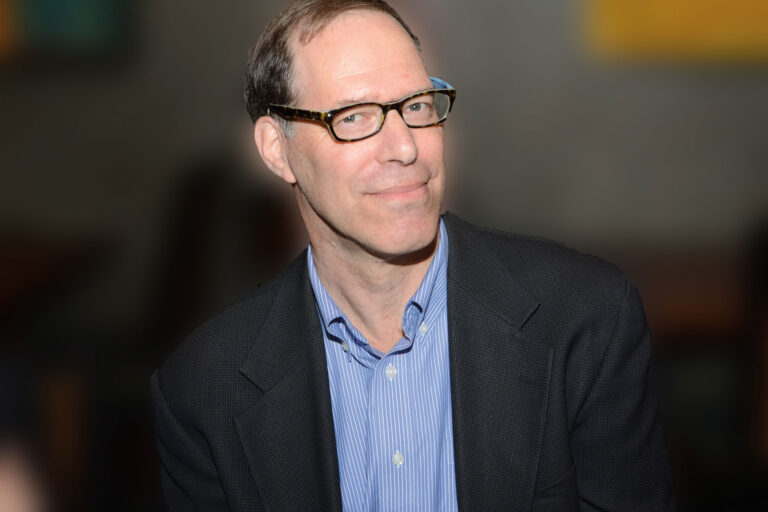

There’s no way to know how accurate various telomere tests are. “There are a few published methods for telomere measurements. Some are better than others in terms of quality control and robustness. The most common method is called the real-time PCR method. We run it in my lab at the Harvard Cancer Center. But it requires expertise to run the test, and there are a lot of variables,” explains Immaculata De Vivo, M.P.H., Ph.D., a Harvard Medical School professor and genetics researcher at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center.

Having just one telomere test — even in a research lab — can’t tell you how fast your telomeres are shortening. This is because we’re not all born with the same quantity of telomeres, and because you’d need a baseline test followed over time to find out how much telomere length you’re losing.

Plus, even if your telomeres are shortening, it doesn’t mean something bad will happen. “And if your telomeres are long, it doesn’t guarantee that something bad won’t happen,” says William Hahn, M.D., Ph.D., a Harvard Medical School professor and chief research strategy officer at Harvard-affiliated Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Should you try telomere testing?

The commercial labs and clinics plugging telomere tests suggest that the results will help you make better lifestyle decisions to slow telomere shortening and increase telomere length.

Is it really possible? “There’s nothing that has been proven to prevent the shortening of your telomeres,” says Hahn.

However, since stress and unhealthy lifestyle habits have been linked to shorter telomeres, it is reasonable to suppose that stress reduction and healthy lifestyle might be beneficial. “There is mounting evidence that a healthy lifestyle buffers your telomeres,” De Vivo says.

Learning your telomeres’ status could then be a wake-up call to change behaviors associated with telomere shortening, such as eating a healthier diet, losing weight, stopping smoking, or reducing stress.

But do you really need to pay for a test to tell you that? It may be easier to adopt healthy habits associated with a longer life.

(Heidi Godman is executive editor of Harvard Health Letter.)