An award-winning journalist, Katie has written for Chicago Health since 2016 and currently serves as Editor-in-Chief.

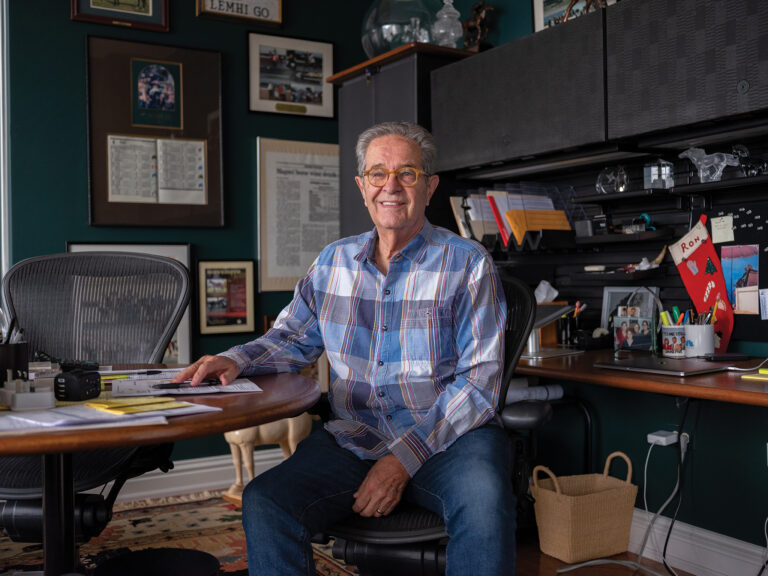

Broadcast journalist Ron Magers reflects on his decades in journalism — and what the future may hold

Fact checked by Shannon Sparks

For 51 years — and an estimated 24,990 newscasts — Ron Magers narrated life for television news watchers. He is quintessential Chicago broadcast media, having started here in 1981.

Magers anchored the 5 p.m. and 10 p.m. newscasts on NBC and later ABC, and he still lives by the clock eight years into retirement. He spends his mornings going through newspapers, blogs, and other outlets. When news breaks, he flips between MSNBC, Fox, and more, studying how each channel covers the topic.

“I used to read with an eye of where does this go next? Who does it affect in our viewing areas?” Magers says. But in retirement, “I’ve learned to be a different kind of news consumer, for my own interests.”

Magers, 79, remains deeply in touch with the state of the world and media today — including the potential implications and benefits of artificial intelligence (AI).

“AI will do a number of amazing things, and there are some amazingly bad people who can’t wait to use it,” he says. “We have to figure it out. We’re going to have to learn it and learn it fast.”

Magers — whose honors include eight Emmy Awards, an Ethics Award from the Society of Professional Journalists, and more — says his greatest concern is that journalism is going away. In January 2024 alone, 528 journalists nationwide were laid off, including 115 at The Los Angeles Times. “Those are the people who cover the everyday events of our lives. Honestly, I don’t even like to talk about it because it scares me so much. We are already a less- informed society.”

Magers’ journalism career began by accident. He grew up in a Washington town of 5,000 people, where many boys spent summers in the fields, baling hay for $1 an hour. But Magers’ friend worked at the local radio station for $1.10 an hour, spinning music in the air-conditioned office. That struck him as the more attractive option.

In subsequent years, Magers attended a handful of colleges but “didn’t stay anywhere long enough to get a degree.” He switched from radio to television in Eugene, Oregon, and ran the two-man local news broadcast with a reporter named Bruce Handler, who had degrees from Northwestern University and the University of Chicago.

“He shared his education with me and taught me journalism and ethics. I’m extremely grateful,” Magers says. The two wrote, edited, and produced their own stories — all on black-and-white film. “We did everything. We were it,” Magers says. “It was going to school every day.”

By the time he retired five decades later, Magers was narrating newscasts with live footage from outer space. “I was there when local television news was growing up,” he says.

And Magers grew up alongside it, through some extremely contentious times in American history, including the Vietnam War. Of the protests, he says, “That was really the first time in America that parents saw their own children questioning their values, questioning whether their parents were doing the right thing for the country. It was a very intense time,” he says.

A decade later, in 1986, Magers remembers covering a parade that Chicago hosted to finally welcome home Vietnam veterans. Half a million spectators watched 200,000 people march down Michigan Avenue to Grant Park. One of the marchers was a mother whose son was killed in the war.

“She woke up that morning, took his picture off the wall, held it over her head, and walked the entire parade,” Magers says. “These are the things that stick — not shaking hands with the rich and famous — the human things.”

Chicago has stuck, too. Magers still lives downtown and says he always will, in large part due to his children and grandchildren. He adds, “There’s a kind of gritty reality to Chicago.” One that he knows intimately from a career telling its stories.