Alex Camp is a freelance journalist with a master’s in public administration, specializing in public affairs reporting, from University of Illinois Springfield.

Strategies help older adults adjust to life with vision loss

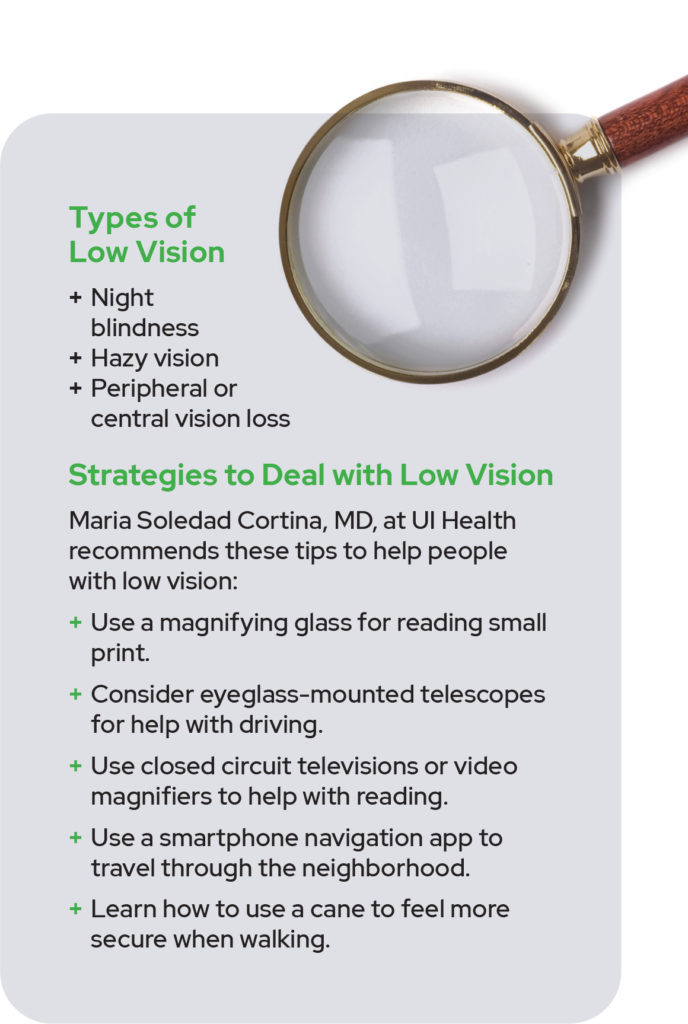

As we age, it can be hard to see well enough to read, drive, or even tell people’s faces apart. Glasses might help, but when contacts, glasses, or surgery fail to improve sight, a person may be diagnosed with low vision — a condition that includes limited vision in dim light or at night, a constricted visual field, and blurred vision, among other issues.

About one in 28 Americans age 40 and over experience low vision, according to a 2015 study by The Vision Council, a nonprofit optical industry trade association. The report also found that vision impairment will steadily increase for the next 20 years, due to chronic illnesses and an aging population.

Aging doesn’t cause low vision, but the condition is more common in seniors because the diseases that contribute to it — glaucoma, macular degeneration, and type 2 diabetes — are more prevalent among older adults.

Dealing with depression

Unsurprisingly, the inability to see clearly often leads to frustration and depression.

One-third of people with low vision experience clinical depression, which is twice the rate of depression in the general population of older adults, according to The Vision Council study. Some 10% of older adults living with vision impairment have a major depressive disorder.

Katrina Stratton, a rehabilitation occupational therapist at Spectrios Institute for Low Vision in Wheaton, has noticed that low vision affects more than her patients’ physical health.

“From my experience, patients are reporting significant impacts that low vision plays on mental health,” she says. “Depression is prevalent.”

Learning strategies to cope with vision loss can help older adults stay engaged and avoid depression, says Maria Soledad Cortina, MD, director of the comprehensive ophthalmology faculty practice, the artificial cornea program, and the General Eye Clinic at the University of Illinois Chicago.

“Attention to the mental health of patients who have lost vision is extremely important,” Cortina says. “The loss of function and independence in many cases can be very hard to deal with. Family support is key.” Her department includes dedicated social workers and can also refer people to mental health professionals and support groups.

Living with low vision

For Michael Mantzke, living with cataracts was a matter of course, as he was born with fully developed cataracts in both eyes. “I went through the majority of my life, with maybe 10% to 20% useful eyesight. The challenge was that there was no technology of any kind to help people with low vision other than large-print books and magnifiers,” says the 66-year-old CEO of a global consulting business in Aurora.

When Mantzke was 35, he developed a detached retina in his right eye. While fixing the retina, doctors removed the cataract. Once the procedure was done, Mantzke had a life-changing epiphany. “I will never forget this: I walked outside, and, for the first time in my life, I saw out of my right eye,” he says. “Up until age 35, the only object I could visually see in the night sky was the moon. The epic moment for me was the first time I saw the night sky as I had never seen it before. I could see Jupiter, Venus, and some faint stars.”

Mantzke says it took about 10 years to find a surgeon to remove the cataract from his left eye. But even after that surgery, he still had low vision because of the way his sight developed. He says his quality of life suffered until the team at Spectrios, a nonprofit organization, gave him helpful visual tools, such as tinted glasses that increase contrast to aid in driving. Finding those solutions made all the difference, he says.

Successful strategies

This is where eye experts can help. Ophthalmologists not only prioritize eye health but also coach people through ways to navigate life with vision loss. They can tell older adults about options to maximize their remaining vision and maintain their independence.

Technology has been a game-changer. People with impaired vision can enlist smartphone and tablet apps to assist with everyday tasks. For instance, Google Maps can help people navigate their neighborhood, and Instacart can help them buy groceries without struggling to read labels in the store. Some apps read text aloud or magnify text, making it bigger and brighter.

Individuals can also learn to rely more on other senses to compensate for vision loss. Hearing an audiobook can be as satisfying as reading a book. And the sense of touch aids in tasks that full-sighted people often take for granted.

“If someone has a hard time seeing their microwave, even when making something as simple as a freezer meal, we can adapt their microwave with raised dots,” Stratton says. “That way, they can feel, which allows them to operate the microwave, even though they can’t read the [words on the] buttons.”

Learning new strategies to deal with low vision helps people become self-sufficient, Stratton says. “Using our sense of touch and hearing helps compensate for vision loss, because it helps teach you to adapt to your environment, and, more importantly, it helps you to keep yourself independent, happy, and healthy in your everyday life.”